Moving Beyond the Limits of Compliance

By: Ken Chapman, Ph.D.

Tony Orlowski, B.S., Civil Engineering, P.E., M.B.A.

To listen to an audio version of this article, click here:

Leaders of potentially hazardous operations face a very real struggle. They have the legal obligation to comply with OSHA regulations and a moral responsibility to keep people safe. They struggle with the fact that while compliance is expected and within their control, experience tells them employee behavior plays the primary role in safe outcomes. How a team member decides to act in a given situation is decidedly not within the leader’s control. Consequently, when safety results aren’t what well-intentioned leaders aspire to, they often double-down on what they can control – compliance. This is all in the hope compliance will eventually win out over what they cannot control – individual decision making. The result is a frustrating cycle of doing the same thing and expecting different results. This is rightly defined as “madness.” It is also wrong on both counts: Compliance has limits no amount of training can overcome. And, while human behavior is imperfect it can be managed.

Compliance

Every line in OSHA’s 29 CFR 1910 was written in blood. Knowing through painful experience what and what not to do is of tremendous value. And, because these regulations are clear and objective, it is easy to measure how we are doing against them whether we are managers or enforcement officers. There’s an old (and true) saying: What gets measured gets done. Let us add a corollary: What is most easily measured is most often measured and is, by the transitive property, what’s most often done. The undeniable value of compliance combined with this self-reinforcing nature is a trap. This trap leads companies to focus almost solely on compliance and leave other worthwhile efforts on the table. Let’s begin by detailing why “compliance only” efforts fail.

Compliance asks others to spend their efforts and resources for the benefit of someone else. The late Nobel Prize winning economist, Milton Friedman, had a wonderful method for predicting outcomes of spending money based on whose it is, and on whom it is spent. There are four categories, but the first two are most instructive here. The first is to spend your money on yourself. In this case, you are likely very careful about how much you spend, and you are going to be certain to get exactly what you want. The second is to spend your money on someone else, like buying a birthday gift for a friend. In that case you’re still careful about how much you spend, but not nearly as concerned about what the person gets. Compliance efforts work out of Milton’s Category II. We are asking people to spend their efforts for the results we want. (If the quality of your employee compliance behavior matches that of the birthday gifts you’ve received over the years, you understand why). Prescribed compliance therefore works best with vast oversite, but management is present only 10% percent of the time an injury occurs. No member of management is present when 90% of incidents occur. This indicates a serious gap in compliance-based safety programs.

It is not and cannot be comprehensive. OSHA regulations are expansive, but it is impossible to write rules for every situation that may arise. The role good judgement plays in safety cannot be effectively replaced by more rules and procedures. Of all significant injuries investigated by OSHA that result in penalties, approximately 56 percent are General Duty Clause violations that are not specifically addressed in the Code. This is another gap a compliance program cannot effectively address.

It will not deter a bad actor, nor will it keep someone from “having a bad day.” Almost everyone will say they agree to comply with safety rules, but not everyone intends to. If there is little chance of being caught, many people will act in a way most convenient to them. Ultimately, no one ever defies their own wishes – only those of others. Often these bad actors are identified by management, but the infractions may not seem significant enough to warrant corrective measures until it is too late. It is also true you don’t have to be a bad actor to have a bad day. Even the safest team members act in ways they normally would not when struggling with personal issues. Approximately 41 percent of incidents investigated by OSHA fall into the “Employee Misconduct” category, and that is because compliance has little influence on them. Compliance-only systems let these people down.

The evidence is overwhelming. Every company has an obligation to follow the law, but even perfect compliance systems cannot guarantee zero injuries, including life-altering incidents and fatalities. Even so, excellent compliance may keep a company out of legal trouble (though that’s not guaranteed), but consider the ongoing costs: worker’s compensation, lost productivity, low morale, and damage to company reputation. These are real business costs organizational leaders are expected to minimize or eliminate. Then consider the human cost. Even if this is hard to quantify it is impossible to ignore. Every legitimate business exists because it in some way promotes the common good. When the net result of its actions is negative, employees, customers, vendors and ultimately society will turn against the organization. It is simply not enough to comply with the law.

The good news is there are effective, objective and measurable ways to fill the gaps left by compliance. It can be done by developing an ownership culture and introducing a moral element to safety. These concepts require further explanation.

Ownership

It is important for every employee to understand the company cannot guarantee their safety. While the company cannot be responsible for them, it is responsible to them. The company is responsible to: eliminate hazardous conditions, provide proper training, make available suitable personal protective equipment and give accurate feedback and appropriate consequences for performance. That said, only the employee can be responsible for their safe behavior, and this can be reasonably expected of any competent adult. Any thought that management can assume responsibility for another person’s safety is not only misguided but dangerous. It is unethical to mislead a team member, even with the best intentions, concerning an issue as important as safety.

If we intend employees to act like competent adults, it’s important we treat them as adults. We don’t allow children to enter many of our facilities, and rightfully so because they haven’t developed the good judgement to keep themselves safe. Good organizations are careful to hire competent adults, and leaders must be careful not to erode that asset by treating them otherwise. Holding people to high and reasonable expectations demonstrates respect. It fosters pride of association and pride of workmanship. Most importantly, it sets up the employee for consistent safe outcomes.

Finally, if we want safety ownership we must promote its benefits for the team member, not the company. When someone is injured there will always be negative impact to the company, but it will never be of the same magnitude as to the person injured or their family. When the focus is on rule breaking, incurred costs or lost productivity, the focus is on the least important part of the issue and by matter of course the organization will lose credibility. By focusing instead on the bigger issue – the human cost – not only does the organization gain moral authority but moves away from Milton’s Category II and toward Category I, where people spend their efforts on themselves, not someone else.

The Moral Element

Safety must always have a moral element to it. Organizations may be hesitant about imposing a moral choice on others, but if safety is viewed as simply a priority to be weighed against others, it will be. By positioning it as a higher-level responsibility safety will emerge as a clear and certain moral choice, because safety is a moral choice whether it is viewed as such or not. Positioning safety as a moral choice means following through with “always putting people first.” It is to step up and embrace our highest responsibility: It is unethical to put one’s self in harm’s way and equally unethical to knowingly allow a coworker to put themselves in harm’s way.

It is also immoral to trade someone’s safety for anything else, including efficiency, profit, personal comfort, or their approval. Efficiency and profit are well understood, but what do we mean by comfort or approval? This means it is not always easy to confront someone who is about to do something unsafe. We may be uncertain as to how the person will react. Or, we may have doubts as to whether we have a proper understanding of the situation. Any or all of these may give us pause or result in a failure to intercede. At such times everyone must understand they are making the decision to trade that person’s safety for their own comfort, and that is always an immoral transaction. The same holds true if we trade their safety to maintain their favorable opinion of us. Placing a coworker’s safety at risk to keep their approval is yet another immoral transaction.

People want to be the hero of the stories they tell themselves. If you ask someone if they would protect another from a dangerous situation, they will almost always respond affirmatively. Use that to mutual advantage and hold people to their highest opinion of themselves. This will require them to either behave consistent with that opinion or force them to construct a new self-image. It’s costly and more difficult to change their self-view. Most team members will not and cannot accept becoming the “moral coward” in their life story.

On the Shop Floor

Ownership and the moral choice will bridge the gaps of compliance, but how can we manage them and gauge progress? For one, we believe every person can be objectively placed into one of three behavioral categories all can agree on, including the persons themselves. It can be done through fact-based evaluation of their actions over time as described in the following paragraphs.

The first category is Safe Behavior is Unacceptable. For a team member in this category proper behavior is unacceptable when it is inconvenient for any reason. There may be a faster, easier or just a more preferred way. In any case, someone in this category cannot be counted on to do the safe thing in the absence of oversite or with little chance of being caught. We can also call this category Non-Compliant.

Next is Safe Behavior is Acceptable. A team member in this category is willing to follow rules whether someone is watching or not. In most compliance-based programs this is often considered the highest level of behavior. But consider what is left out. If the rules are insufficient, incomplete or just wrong, they will still be followed. If this employee is told to do something unsafe by their manager, they are unlikely to question it. Also, following the rules applies only to them. If a coworker is about to do something unsafe, it’s the other person’s concern, not theirs. This category can also be called Compliant.

The final category is Unsafe Behavior is Unacceptable. For this team member acting unsafely is never an option whether an established rule exists or not. They will speak up any time they see a hazardous situation or a coworker about to put themselves in harm’s way. And they will speak up even if it creates discord, discomfort or disapproval. They do this because it is the right thing to do. This is a team member who acts out of their highest opinion of themselves. This can also be called Ownership.

A team that fully understands these definitions and operates in an environment of high trust, can, based on real observations of behavior over time, confidently and objectively place every employee into one of the three categories. We have found it helpful to let the person’s direct supervisor start the evaluation and allow his or her peers and other managers to challenge or support the assessment, careful each comment is fact-based. When done properly, a person may not like the category in which they are placed, but it will be difficult for the team member to disagree. Newer employees who have not established a history should be placed in the lowest category (non-compliant) until they demonstrate, through their actions, they belong elsewhere.

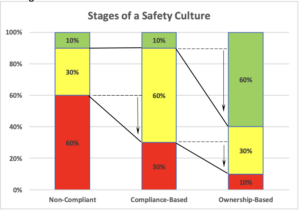

We’ve found it useful to color-code (Red: Non-Compliant, Yellow: Compliant, Green: Ownership) on manning charts as a visual aid to quickly identify where management attention is needed. It is also helpful to graph the distribution of the entire organization to better determine the current state of the safety culture. These three distinct stages are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

An organization with a majority in the Non-Compliant (Red) category likely places little emphasis on safety, believing it the employees’ responsibility to comply with safety rules. Team members may be undertrained, have improper tools or procedures to work safely, or not understand the significance of the rules. Some will be effectively compliant (Yellow) simply out of concern for their personal well-being, but fewer than ten percent will demonstrate ownership (Green) and watch out not only for themselves but for coworkers as well. If you have a similar distribution to this, your program is largely non-compliant and can be expected to have incident rates well above the national average. Frequent occurrences of significant injuries and/or fatalities describe your world.

When an organization decides to take safety seriously, they typically focus on compliance and you will see a distribution similar to the middle graph. A majority of team members will fall into the Compliant category, but a significant portion will remain non-compliant. Those are either “Good” employees who take shortcuts to get the job done, or bad actors who have been deemed minor violators. In short, compliance, or operating out of Friedman’s Category II, hits an inevitable ceiling because we don’t expect team members to be responsible for themselves, so they are not. Ownership remains below ten percent because the “ownership” focus is no greater than in non-compliant systems. If you have a distribution similar to this you can consider your program largely compliant, and incident rates will be close to and even below industry average. However, you will still experience significant injuries and on occasion, fatalities.

As the organization moves toward ownership, the distribution will change again. A majority will find unsafe behavior unacceptable, both for themselves and the people around them. The influence of this majority will make it uncomfortable for others to stay in the compliant category. Non-compliance will not be tolerated. The non-compliant are either new or in danger of leaving the organization; there are no long-term employees in this category. This distribution denotes a largely ownership-based program. Incident rates will be in the top quartile, and significant injuries will be rare or non-existent.

It’s important to note where effort is concentrated in moving from one system to another. When moving to compliance from non-compliance, all effort is focused on reducing negatives (non-compliers) and management shoulders the entire burden. Not everyone can participate because not everyone is knowledgeable enough to do so. In contrast, moving from compliance to an ownership model focuses most effort on positive change – creating more owners – and less on the negative. As ownership improves the ratio becomes more and more favorable. Best of all, team members and their behavior are at the center of the effort.

Once you determine where you are, you must have a means to move confidently in the direction you want. Central to any ownership program is how you handle mistakes and poor behavior. Human behavior isn’t perfect; it never has been and it’s unreasonable to think it ever will be. Even the best people make mistakes, so the most useful way to manage what is inevitable is to treat mistakes as learning experiences.

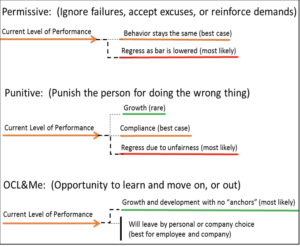

Unfortunately, most managers don’t know how to do this. In the face of undesirable behavior, they typically respond in one of two ways: permissively or punitively – and both usually lead to even worse behavior. A better response, OCL&M (Own it, Correct it, Learn from it and qualify to Move on) is a true up-or-out system that addresses the shortfalls of both and uses mistakes as opportunities for growth. These approaches are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Managers can be permissive in several ways. They can ignore the unsafe behavior or pretend not to see it. This is often done because the act seems relatively minor and if addressed must be either punished or risk weakening the rule. At best this leads to passive acceptance of the behavior and is regressive as both parties know the act has been implicitly condoned and the bar is not in reality set as high as stated. Another way to be permissive is to accept excuses when the person rationalizes the behavior. The manager may reprimand the employee, but in the absence of any real consequence the message is clear: The standards for what we accept are lower than we say. A particularly sinister permissive response is retraining. It’s sinister because it provides cover for both parties: the employee is sentenced to re-education and the company responds compassionately in its obligation to properly train. Both parties know, however, this dodges the real issue and future outcomes are predictable. An unacceptable intentional behavior goes unaddressed and will likely arise again.

Punitive is much simpler but equally ineffective. The company sets rules and consequences for violating the rules. If a team member is found in violation they suffer the consequences. In rare cases this may lead to improved behavior where the violator sees the error of his ways and complies in the future. The more likely response is resentment due to the perceived unfairness of the punishment. It is human to make mistakes, and he knows you have made them, too. Others have done similar things and not suffered a consequence. Because the perceived unfairness breeds resentment, behavior worsens. Only now the unacceptable behavior goes underground as the employee redoubles his effort not to get caught again.

Contrast these approaches with OCL&M. If a manager observes improper behavior, the first step is to ask the person to explain the situation in their own words. This provides them the opportunity to own their behavior in a respectful exchange between two adults, as opposed to a parent/child dynamic. If the person owns the act they are also likely to own the outcome and feel a responsibility to correct it as best they can. This sets up an opportunity to demonstrate they have learned from the mistake and grown as a team member. If a team member sincerely goes through those three steps after making a mistake (owned it, corrected it and demonstrated they have learned from it), they have earned the right to move on. That is, truly move on, with nothing hanging over their heads or anchoring them to the past. On the other hand, if a team member refuses to accept responsibility for their actions, there must be a consequence. This means OCL&M can be fairly applied in identical situations yet have very different outcomes. The outcome will be based entirely on the response of the individual. It is consistent, fair and flexible and allows mistakes while maintaining accountability. The only forward path is up. This is the outcome which leads to a stronger team.

If you are disappointed with the results of your compliance-based safety program, consider “ownership” as your path forward. And while the concepts discussed here are largely common sense, there are reasons they are not in use in most organizations. It’s essential to identify these reasons so they don’t become roadblocks in your own efforts.

It can be argued the three stages of a safety culture are a natural progression. It is difficult to have ownership before mastering compliance, and compliance comes only after understanding the consequences of non-compliance. While these are logical steps upward, most organizations remain unaware of the next level. Those in non-compliant systems truly believe employees should just do the right thing. Organizations fully dedicated to a compliance system believe more controls will ultimately do the trick. Only when leadership is convinced of the need for a better way can they move on.

In addition, while these approaches are not difficult to understand, they are neither intuitive nor easy. In contrast to compliance where good performance can be achieved by properly “checking all the boxes”, safety excellence is no easier to attain than any other form of organizational excellence. “Ownership” requires training and sustained effort to effectively implement.

Finally, many leaders are alarmed by any perceived challenge to their compliance efforts. Their true view of team members is as less than capable, not as competent adults. As such they must be taken care of and tightly controlled. These leaders may also lack confidence in senior managers’ willingness to hold people properly accountable, and they may be unwilling to hold those managers accountable themselves. Harboring these views, they are understandably concerned about potential liability in an ownership culture.

But this is a misunderstanding of the vital relationship between compliance and ownership. Compliance and ownership are not either/or, and ownership takes nothing away from compliance, nor does it involve risk not already present. The two compliment and leverage each other for optimal outcomes. Compliance is the foundation upon which Ownership stands. Team members must know the rules, safe work practices and the mutual benefits of working safely. That said, Ownership moves compliance out of the sphere of watch, catch, punish and into the sphere of healthy self-interest. And best of all, it appeals to the team members’ highest opinion of themselves.

For more information, visit www.SafePath.solutions

RELATED RESOURCE:

Listen to this 24 minute podcast interview “Safety Beyond The Numbers” on Brain Chatter podcast with Tony Orlowski